Title: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Rooney on March 04, 2014, 09:52:13 PM

()

Elections are what bring us all together at this site. We love the hand shaking, back slapping, ass-ahem-baby kissing that makes an election the greatest show on earth. There is no denying that of all elections the quadrennial calumny of the United States Presidential contest is the gaudiest and grandest of all elections in this Land of the Free.

However, which elections were the best and which were critical and commercial flops? The United States has experiences fifty-seven national contests. Some are historic battles of ideologies, others a game of Trivial Pursuit while some were nothing more than flops.

In this list I will count down all fifty-seven of these elections from the most mundane to the most exciting. In this list I will not take the ideology or politics of the winner into account. For example, in a comparison of the 1836 election and the 1912 election I much prefer the victor in 1836. However, there is no denying that 1912 has many more intriguing, unique and entertaining factors. Thus, even though the victor of 1912 is not to my ideological liking the election is an excellent one that will attain a high ranking.

Now I am off to analyze the campaign trail. After all, while elections may very well make history and alter the policy of a nation we all know what they are supposed to do: entertain us.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Rooney on March 04, 2014, 09:54:06 PM

#57: The Election of 1820

()

This crazy train starts out with a leisurely caboose ride. In 1820 the nation was riding high on a time of unchecked pork barrel politics and internal “improvement” spending spearheaded by the mild-mannered President James Monroe of Virginia. Leading the nation in a time known as “The Era of Good Feelings” Declaring that political parties were “incompatible with free government” Monroe had sought in his first term to coopt members of the defunct Federalist Party into the Republican fold. Known to some as the “Young Washington”, Monroe’s one-party rule produced a lull in election action but not in political troubles.

The main reason why the election of 1820 is such a bore is that it could have been an incredible contest if there had been any formal opposition to Monroe and Vice-President Daniel Tompkins. In 1819 the heavy borrowing and inflationary monetary policies of the U.S. government brought about a specie strain that led to the Panic of 1819. This first great economic struggle could very well have caused an issue for Monroe’s reelection had he faced an opponent willing to run against the Second Bank of the United States and the lose money policies of the Madison and Monroe governments. Additionally, the sectional trouble caused by the Missouri Compromise could also have led to an anti-slavery candidacy from a Northern or Western candidate to oppose Monroe. Alas, there was no vessel and so Monroe, a former wily politico turned pacific executive, was reelected by the margin of 227 to 1.

The reason why this election is the most boring in American history is the lack of good drama. This is not to say that there was no drama in the election. There simply was no memorable drama. There was the surprise vote for John Quincy Adams from Baptist lay preacher William Plummer of New Hampshire. While it would be nice to believe the story that he voted for Adams in 1820 in order to ensure that only Washington was unanimously elected close scrutiny has shown this dramatic response is quite tepid. It appears that Plummer voted for Adams because he thought Monroe to be a “mediocrity” and Tompkins to be “negligent” of his duties as vice-president. These are very logical conclusions and while logic is nice it is hardly dramatic.

There was also a brief struggle over whether or not Missouri’s electoral votes would be counted. This came down to the technicality that Missouri was not actually a state when it cast its electoral votes for Monroe. New Hampshire proved itself to once again be the only state that wanted to make this election interesting when Congressman Arthur Livermore of the Granite State raised his voice in protest of the Show Me State’s electoral votes. The Senate, however, destroyed all drama by passing a resolution allowing for the state’s electoral votes to count provided they did not change the outcome of the election. This could have been a great controversy had the election been so close that the state’s three electoral votes been the linchpin for a presidential victory. However, this was not the case and is merely a legal footnote in the history of elections.

Monroe’s near unanimous reelection was a major personal victory for him and for his one-party state. If the election of 1820 is to teach us anything we should take from it two lessons. The first is that one-party states are either boring or tyrannical. Sometimes they are both! The second lesson we should take is that while political parties can be annoying they make elections a heck of a lot more fun.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: FEMA Camp Administrator on March 04, 2014, 09:59:40 PM

Not much to comment on, but I do intend on following this series until its conclusion.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: I Will Not Be Wrong on March 04, 2014, 10:02:43 PM

Will Definantly continue reading this.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: PPT Spiral on March 04, 2014, 11:24:48 PM

This is wonderful. Count me as another person who will closely follow.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Rooney on March 05, 2014, 10:47:55 PM

#56: The Election of 1804

()

Thomas Jefferson’s reelection campaign was hardly a dramatic or interesting election. His first term as president is fascinating, no doubt. In his first term he had slashed taxes, reduced Adam’s bloated navy, destroyed the Additional Army, purchased Louisiana, increased free trade on the Atlantic and managed to sever the close alliance of the Barbary States. While the constitutionality of Louisiana and the mission to Tunisia, as well as the later Lewis and Clark Expedition, stands on shaky ground the American people always seem to love constitutional violations. In 1804 President Jefferson was highly popular and looked forward to a sunny second term.

Jefferson had also spent his first term dedicated to coopting Federalists into the Republican Party. “We are all Federalists, we are all Republicans” he waxed eloquent in his first inaugural address, one of only two public speeches he would make as chief executive. If only the current occupant of the White House was so economical with his words. Jefferson rejected highly partisan judicial appointments and broadly interpreted the constitutional powers of his office in order to appeal to those Federalists excluded by the High Federalists and the Essex Clique. Thus, the Federalist Party was a weak shadow of its former self when it nominated former Minister to France Charles Cotesworth Pinckney for president and former Senator Rufus King for vice-president. Pinckney, who was once mocked in a sermon by the mercurial Reverend Timothy Dwight, never stood a chance outside of Connecticut.

This scenario makes for one boring election. Landslides are usually boring. They are like when the Miami Heat plays the Detroit Pistons. It is fun to watch a beat down for a little while but pretty soon you turn off the TV and open up a book on moral philosophy. This is not to say that there were not some exciting and dramatic moments in this election but none of them had anything to do with the ultimate outcome.

One amazing moment of 1804 was, of course, the field of honor at Weehawken. The Burr-Hamilton Duel was attached to an election in 1804, just not the presidential campaign. President Jefferson had already dropped Burr (“The American Cataline”) for the jovial, doddering Governor George Clinton of New York. As all students of history know, Burr shot Hamilton over Hamilton’s machinations against him in his ill-fated quest for the New York governor’s post. The story of the duel and Burr’s later dreams of an American Empire stretching from Mobile Bay to Monterrey is one of the epics of American History. However, it plays very little to no role in the reelection of Jefferson. In fact, it played no role at all. Thus, this grand drama has nothing to do with Mr. Jefferson’s reelection.

There is also the story of Jefferson’s gunboats. The Federalists mocked Jefferson for his gunboat fleet. Gunboats were far cheaper to maintain than any ship-of-the-line so Jefferson, a penny pincher in public and a spendthrift if private, obviously fell in love with them. Fifteen gunboats floated across the Eastern seaboard to defend the nation from piracy. In September 1804, a terrible hurricane off the coast of Savannah, Georgia, picked up Gunboat Number One and tossed it into a cornfield. The proprietor of the cornfield actually tried to sue the government for damages! The Federalist campaign mocked Jefferson by stating that he had finally found a good use for his gunboat: as a scarecrow. While these gibes made victory starved Federalists smirk and giggle they are merely fun historical trivia. They added nothing to the campaign itself and added no drama to the final outcome.

A third interesting story that came from the election was the scurrilous charges that Jefferson had sired children from one of his female slaves. In September 1802, political journalist James T. Callender, a disaffected former ally of Jefferson, wrote in a Richmond newspaper that Jefferson had for many years "kept, as his concubine, one of his own slaves." "Her name is Sally," Callender continued, adding that Jefferson had "several children" by her. Jefferson never commented on these accusations and Sally, who could not write, never recorded any letters or documentation to back up the story. Callender, who was found drowned in less than three inches of water in 1803, was a well-known political crank and scandal monger. While the faltering Federalist campaign tried to make “Black Sal” a campaign issue it never gained traction. This was not the first time that base rumor mongering would be used in an election but many times such dark tactics can dramatically effect an election. In 1804 this was not the case.

The main reason why the election of 1804 is the second most boring presidential election is that there was no drama. While Jefferson and Pinckney are “big names” in American history neither ran an active campaign. Unlike in 1796 and 1800 both parties were docile and tame. There was no incredible politicking for control of state legislatures or wonderfully juicy accusations of atheism and monarchism. The campaign was bland and calm. That makes for a nice tea party but a downright dull presidential campaign.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Oswald Acted Alone, You Kook on March 05, 2014, 11:26:30 PM

It may have been pointless, but it was the first election under the new rules.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Rooney on March 06, 2014, 01:31:56 PM

It may have been pointless, but it was the first election under the new rules.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Rooney on March 06, 2014, 02:50:26 PM

#55: The Election of 1816

()

1816 ends up at the number fifty-five spot for more or less the same reason that 1820 and 1804 are ranked low: it was a one-party show. James Monroe’s first election to the presidency boasted more struggle than the previous two elections, no doubt. However, the struggle was primarily in the Democratic-Republican caucus. This makes for one important episode but when compared to elections to come this one blip of excitement does not even register on the scales.

The end of the Madison Administration ushered in a civil, silent election. The War of 1812 was over without victory, the Second Bank of the United States was in full swing and the nation was slowly recovering from the economic disaster of the war. One would think that in such an environment a strong Federalist challenge may well have arisen against Little Jemmie’s government. The great trouble was that the Federalist’s opposition to “Mr. Madison’s War” and the meeting of secessionist High Federalists at the Hartford Convention had made the party as dead as their founder, Hamilton. Federalism was no longer even relevant in Massachusetts or Connecticut. “Our two great parties have crossed over the valley and have taken possession of each other’s mountain,” former Federalist President John Adams wrote. Yes, the Federalists were no longer a legitimate threat to anyone, not even to themselves.

The great drama of the campaign was the Democratic-Republican Congressional Caucus. This could very well have been an incredible battle of egos. Potential candidates for the Democratic-Republican nomination included Monroe, Secretary of War William H. Crawford, House Speaker Henry Clay, New York Governor Daniel D. Tompkins and former Senator and the Hero of New Orleans Andrew Jackson. Clay, Jackson and Tompkins bowed to the inevitable. While New York Republicans grumbled about the “Virginia Dynasty” all they could do was grumble. Crawford ran a spirited race in which he questioned Monroe intelligence and vision, but the well-liked Monroe was always the front-runner. The Congressional Caucus of March 1816 was close but the Monroe was the winner by a decently wide margin. The overwhelming selection of Tompkins for vice-president concluded what could have been a wild, crazy caucus.

The Federalists failed to even nominate a candidate for the general contest. Senator Rufus King was nominally selected as the candidate but he knew from the very beginning that he was a sure loser. Long before the electoral votes were counted in December 1816 King had commented: “Federalists of our age must be content with the past.” It is to be applauded that Senator King realized the fight was lost but that does not add to the joy of the campaign.

The contentious fight for the Democratic-Republican Party nod proved to be quite anti-climactic. So too did Senator King’s pathetic candidacy. Monroe, the only man to serve as both secretary of state and secretary of war at the same time, coaxed to victory without writing and letter of issuing a statement. The main reason why this election is ranked low is because it was yet another one party romp. The one party romp may well have been interesting had more legitimate candidates jockeyed for the Republican presidential nod but that did not occur. While there was a controversy over whether or not Indiana’s electoral votes would count the issue was worked out quickly and with no issue. Additionally, it is not as if the 3 electoral votes from the Hoosier States mattered for the final outcome.

I believe that the former Federalist newspaper the Boston Daily Advertiser put the election of 1816 the best: “We do not know, nor is it very material, for whom the Federalist electors will vote.” John Randolph of Virginia further commented that amongst the people there was a, ‘Unanimity of indifference if not approbation.”

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Rooney on March 07, 2014, 12:30:04 AM

#54: The Election of 1996

()

“The era of big government is over,” President Bill Clinton declared in his 1995 State of the Union Address. With the help of known troll Dick Morris he was able to trick the nation into actually thinking what he said was true. Yes, Clinton is one of the master politicians of our time and that is the reason why the 1996 election- his triumphant reelection- ranks as #54 on the list.

The election of 1996 could have been the Waterloo for Clinton and his curious Little Rock Crew. His wife had been temporarily silenced by her health care beat down, Clinton had fumbled Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell and the Republicans were in a post-Poppy Bush resurgence. A strong Republican presidential nominee running on eloquent conservative, free market principles could very well have evicted Bubba and his buds from the Oval Office. It was the Grand Old Party’s golden opportunity to settle the score with their most successful and hated rival. They gave the world Bob Dole.

The main reason why 1996 falls into the #54 spot is that the election was not very exciting. There were no great moments of drama, no epic arguments and no real discussion of contentious issues. Dole and Clinton agreed on many core issues: national defense, education, gay rights and welfare reform. Dole, when not talking about himself in the third person or stage diving, muttered about a 15% tax cut but never explained how he would get this tax cut done, how he would pay for it or how this loss of revenue would affect his pledge to balance the budget. In the 53rd quadrennial contest Dole more or less proved that he was a relic of the 1960s. He referenced the Brooklyn Dodgers as a baseball team and appeared sleepy at the debates. Clinton rarely fell below 50% in the public opinion polls and led Dole in different tracking polls by margins ranging from nine to fifteen points. At no point was the election’s results in doubt and Bob Dole did little to fight back.

Massive landslide reelection victories do not naturally deem an election boring. In 1972 and 1964, for example, upstart senators were able to manipulate party rules in order to surpass establishment candidates. Even though their nominations led to the incumbent winning by a wide margin the election is still thrilling because one was able to witness the meteoric rise and noble decline of the upstart underdog. In 1996, Pat Buchanan was the underdog who had managed to beat Dole in the New Hampshire Primary. Beaten in New Hampshire in all three of his quests for the presidency, Dole commented that he realized how the Granite State got its name: “It’s tough to crack.” Buchanan, like Ron Paul in 2012, attempted to use the machinations of party to attain the nomination but was stopped time and time again by establishment party attorneys and bigwigs. A Pat Buchanan vs. Bill Clinton race would have showcased real differences between candidates and made the election of 1996 a memorable race. Buchanan would have won 39% of the popular vote and 60 electoral votes but the race would have been a real difference. It would have offered the American people a choice, not an echo.

H. Ross Perot was not even able to add flavor to the campaign’s stoic soup. His Reform Party was plagued by intraparty rivalries and laws which set up obstacles for third parties. Perot was unable to attend the debates because the League of Women Voters had had their power over the debates snatched from them by the cold, iron grasp of a major party amalgamation known as the Commission on Presidential Debates. Despite lawsuits, the CPD set the bar so high that Perot was not allowed to talk straight to the American people as he had in 1992. Plagued by ill health and a party that was not totally united behind the Lilliputian leader, Perot was a nonentity in the 1996 race.

In the end the main reason why 1996 is ranked as #54 on the list is because it offered no surprises and took no chances. The establishment Republican ran a lackluster campaign against a popular incumbent. The economy was decent and the nation was not embroiled in any unpopular wars so the incumbent won by a large margin. It was a “nice” little election. Yawn.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Del Tachi on March 07, 2014, 02:11:32 PM

Sure 1996 is boring, but number 54?

1936, 1956, 1924, and a few other national elections are infinitely worse.

1936, 1956, 1924, and a few other national elections are infinitely worse.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: True Federalist (진정한 연방 주의자) on March 07, 2014, 02:45:20 PM

Sure 1996 is boring, but number 54?

1936, 1956, 1924, and a few other national elections are infinitely worse.

1936, 1956, 1924, and a few other national elections are infinitely worse.

I would hardly call 1924 and the Klanbake a boring election, even if most of the excitement was at the DNC.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Oswald Acted Alone, You Kook on March 07, 2014, 06:50:14 PM

Of all the re-match elections, this is your pick? 1832, 1900, 1944, 1940, 1956, and 1984 are all worse/ more boring.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: FEMA Camp Administrator on March 07, 2014, 07:12:12 PM

Of all the re-match elections, this is your pick? 1832, 1900, 1944, 1940, 1956, and 1984 are all worse/ more boring.

1832 had Henry Clay losing, something that never gets old. If you mean 1828, where-in Jackson came back to beat Adams after the election four years earlier, that was pretty epic. 1900 is a McKinley victory, which is never boring. 1940 saw the British sabotage of an American political party's convention and its sequel took place with the backdrop of one of the most epic conquests of human history. 1956 and 1984 at least had good results, and the 1984 Dem primaries would've been pretty cool to see play out.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Mechaman on March 07, 2014, 07:22:16 PM

Of all the re-match elections, this is your pick? 1832, 1900, 1944, 1940, 1956, and 1984 are all worse/ more boring.

What is this? I don't even. . . . . .

1832 was pretty much a showcase of the then new political alignment in America. THe narrative was entirely about Jackson vs. "OMG EVIL BANKERS!", something that isn't really boring at all.

1900 had the return of William J. Crazyman Bryan and was basically a AMERICA RULES! campaign on the GOP side. While it might've been a cakewalk, both sides were out in style, something that can't be said about 1996.

1944. . .. . are you f***ing high? Did you forget World War II existed?

1940. . . . okay, a little dull compared to 1944, but the backdrop of the election is certainly notable.

1956. . .. . okay, I actually might agree with you on this one. In fact, 1956 and 1996 could be twins.

1984. . . . Reagan's re-election. The campaign was hardly "boring".

I don't remember the 1996 election campaign. That's how "boring" it was.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Rooney on March 08, 2014, 04:22:58 PM

I will get two updates in tonight. Thank you for your patience. I teach special education and have had a huge amount of IEP paperwork for the start of the month. You guys are awesome for waiting.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Rooney on March 08, 2014, 06:17:08 PM

#53: The Election of 1792

()

George Washington’s triumphant reelection in 1792 is ranked as #53 because it was a great deal of humdrum with only one major moment of dramatic suspense. This in itself is a disappointment because the emergence of the First Party System in the United States promised far better than what the people were given.

Haunted and depressed by divisions in his government, President George Washington had intended to refuse to seek reelection. The emergence of Hamilton’s Federalists and Jefferson’s Republicans had caused Washington much torment. While he leaned strongly toward Hamilton and the Federalists, the general hoped that the emergence of factions could be nipped in the bud. This was not to be and Washington’s own strong support for the National Bank, tariffs, whiskey taxes, debt consolidation and other Hamiltonian centralization plans did little to heal the divisions.

The race for president in 1792 was never in doubt. Washington’s popularity was no longer at its height as it was in 1789, but he was still the hero of the Revolution. His reelection was never in doubt. The reason why 1792 could have been a great race lies in the vice-presidential contest. With Washington assured one vote from every elector the second electoral vote was the one to fight over. Vice-President John Adams assumed that he would be the easy choice for vice-president. In a system with no parties this very well would have been the case. However, anti-Hamiltonians put forward three opposition candidates to the stout vice-president. Governor George Clinton of New York was the principal anti-Hamiltonian vice-presidential candidate but five votes were given to Thomas Jefferson and Senator Aaron Burr. Anti-Federalists vice-presidential candidates managed to win 55 electoral votes to Adam’s 70. Upon reading the results Adams later commented to his wife Abigail, “Damn them, damn them, damn them.” The race for vice-president was far closer than the crotchety Adams had expected or wanted.

The vice-presidential contest is a testament to the fact that there was obvious resistance to the Washington-Hamilton system. The fact that George Clinton, with no campaigning or even a letter stating he would accept electoral votes, managed to win 50 electoral votes shows that the Federalist system was propped up strongly on the shoulders of Washington Rex. Washington chose to run for reelection in 1792 out of fear that a partisan campaign for the top office would weaken the new republic and toss the system into civil war. It is in the opinion of this writer that Washington truly feared that the Federalist system that Hamilton had built would collapse if he was not there to be the face on the billboard of the unpopular programs. The general and the president was to be proven correct when Adams became president.

1792 is an election that could have been a great one but in the end was tame and calm. That is to be expected when George Washington was a candidate but that does nothing to further its place in campaign history or, more importantly for me, the ratings.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Rooney on March 08, 2014, 06:20:31 PM

#52: The Election of 1808

()

()

The election of 1808 winds up at the number fifty-two on the list. This marked the last campaign of Jefferson’s America and the old First Party System. The Federalist Party was given a major shot in the arm by Thomas Jefferson’s unpopular Embargo Act. Throughout his presidency Jefferson had made it a habit to ignore his classical liberal roots. The Louisiana Purchase, the Lewis and Clark Expedition and the First Barbary War were all highly unconstitutional. However, they all pale in comparison to the Embargo Acts. Known as the Damnbargo in Federalist New England, the embargo betrayed all of Jefferson’s work in his first term to encourage free trade and instead forced recession and trade war onto the United States. The arrests of innocent merchants trying to make a living only reminded Americans of the Federalist regime of John Adams and his arrest of innocent printers. The Federalist Party, which was on the ropes in 1804, was given a boost by the unpopular new law.

The fact that the Federalists had an unpopular law in their favor is one of the reason why the election of 1808 places at fifty-two on the list. The Federalists, in theory, could have made a triumphant return to the White House on the back of Jefferson’s economic fumble. However, this was not to be the case because the Federalists were old hat by 1808. The candidate they produced was a nationally famous also-ran. Former American Ambassador to France Charles Cotesworth Pinckney (of XYZ Scandal fame back in the year 1798!) was informally selected as the Federalist Party presidential nominee and former New York Senator Rufus King was selected as his running-mate for the second time in a row. The same uninspired ticket from 1804 was hardly enough to energize Federalist candidates for state assembly in New York or state voters in Pennsylvania. The party of Hamilton was a as dead as its founder.

1808, however, was not a completely anti-climactic contest. The 1808 Democratic-Republican Caucus was a bitter affair that would spill over into the general election and the electoral vote canvass in December 1808. Secretary of State James Madison, Jefferson’s long-time protégé and acolyte, was the front-runner for the party’s presidential nod but faced opposition from sitting Vice-President George Clinton and popular former Virginia Governor James Monroe. The aging Clinton, who secretly yearned for retirement, was put forward as the candidate in opposition to the “Virginia Dynasty.” Clinton did not actively seek the nomination and would not be given it. Monroe actively wrote letters to congressmen stating his interest in the presidential nomination but this small time campaigning also proved to be useless. Madison had spent the better part of a year convincing Republicans in Congress that he was the choice of Jefferson, who was still the idle of the Democratic-Republican brass. The final tally for the presidential nod at the caucus was hardly close: Madison 83, Monroe 3, Clinton 3.

On the day in December when the electoral votes were cast Madison won an easy victory over his hapless Federalist challengers. Pinckney’s ability to win almost all of New England, Delaware and three electors from North Carolina are a testament to an election battle that might have been. Had Chief Justice John Marshall tossed his hat into the presidential ring perhaps a stronger race would have happened in 1808? It is to be noted also that there were some divisions in the Democratic-Republican fold. George Clinton attained 6 electoral votes from his native New York while Monroe won over 4,000 popular votes from his native Virginia. While these defections did not manage to make a difference in the overall election these defections are to be noted as factors that may have caused trouble to Jefferson’s party had the Federalist Party had a stronger ticket.

In the end the reason why the election of 1808 is ranked at number fifty-two is because it fell at the end of the First Party system. The Damnbargo and the anger from New England gave it some drama as did the opposition to Madison at the convention but in the end it had to fall in the bottom part of the list. The election offered much promise but in the end delivered very little action.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Oswald Acted Alone, You Kook on March 08, 2014, 06:25:55 PM

Both 1940 and 1944 were pretty easy victories for FDR, and it was very obvious he was going to win in both years. Wilkie and Dewey did better than Landon, but there wasn't much of a challenge between the two elections. Besides, who would, as Lincoln put it, switch horses in the middle of the stream?

1832 had Jackson win easily against someone who made a deal to keep Jackson out of office, if anything the previous election was the re-alignment.

1900 was another failed attempt by William J. Bryan. I guess this should be a little higher for Theodore Roosevelt, though.

1956 of course is 1996 in 40 years; a peacetime election with a popular president.

Jesus couldn't beat Reagan in 1984. Reagan was at the height of his popularity at that point. The Democrats couldn't get anyone good enough to oppose Reagan.

Also, since Rooney posted again, 1792 has got to be one of the least important too.

1832 had Jackson win easily against someone who made a deal to keep Jackson out of office, if anything the previous election was the re-alignment.

1900 was another failed attempt by William J. Bryan. I guess this should be a little higher for Theodore Roosevelt, though.

1956 of course is 1996 in 40 years; a peacetime election with a popular president.

Jesus couldn't beat Reagan in 1984. Reagan was at the height of his popularity at that point. The Democrats couldn't get anyone good enough to oppose Reagan.

Also, since Rooney posted again, 1792 has got to be one of the least important too.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Mechaman on March 09, 2014, 01:58:45 PM

Both 1940 and 1944 were pretty easy victories for FDR, and it was very obvious he was going to win in both years. Wilkie and Dewey did better than Landon, but there wasn't much of a challenge between the two elections. Besides, who would, as Lincoln put it, switch horses in the middle of the stream?

1832 had Jackson win easily against someone who made a deal to keep Jackson out of office, if anything the previous election was the re-alignment.

1900 was another failed attempt by William J. Bryan. I guess this should be a little higher for Theodore Roosevelt, though.

1956 of course is 1996 in 40 years; a peacetime election with a popular president.

Jesus couldn't beat Reagan in 1984. Reagan was at the height of his popularity at that point. The Democrats couldn't get anyone good enough to oppose Reagan.

Also, since Rooney posted again, 1792 has got to be one of the least important too.

1832 had Jackson win easily against someone who made a deal to keep Jackson out of office, if anything the previous election was the re-alignment.

1900 was another failed attempt by William J. Bryan. I guess this should be a little higher for Theodore Roosevelt, though.

1956 of course is 1996 in 40 years; a peacetime election with a popular president.

Jesus couldn't beat Reagan in 1984. Reagan was at the height of his popularity at that point. The Democrats couldn't get anyone good enough to oppose Reagan.

Also, since Rooney posted again, 1792 has got to be one of the least important too.

Again, I'll re-quote my post:

Of all the re-match elections, this is your pick? 1832, 1900, 1944, 1940, 1956, and 1984 are all worse/ more boring.

What is this? I don't even. . . . . .

1832 was pretty much a showcase of the then new political alignment in America. THe narrative was entirely about Jackson vs. "OMG EVIL BANKERS!", something that isn't really boring at all.

1900 had the return of William J. Crazyman Bryan and was basically a AMERICA RULES! campaign on the GOP side. While it might've been a cakewalk, both sides were out in style, something that can't be said about 1996.

1944. . .. . are you f***ing high? Did you forget World War II existed?

1940. . . . okay, a little dull compared to 1944, but the backdrop of the election is certainly notable.

1956. . .. . okay, I actually might agree with you on this one. In fact, 1956 and 1996 could be twins.

1984. . . . Reagan's re-election. The campaign was hardly "boring".

I don't remember the 1996 election campaign. That's how "boring" it was.

I'm not contending these are Oscar nominations here, just that they don't fall into 1996 territory. An argument that is extremely easy to make if you aren't blind/deaf.

On 1832 I was referring more to the explosion of media involvement in the race compared to the previous ones. THere was a lot more money and a lot more inventive politicking in the 1832 race than in 1828. THe realignment began in 1828, obviously, but the usage of open ad politics exploded in 1832 when Jackson ran for re-election.

1940 and 1944, just because a race is easy doesn't mean it is boring. The FDR campaign commercials, like the "HEll Bent Till Election" cartoon are classics. Whatever you may say about how easy these were, there was still a lot of interests in the races and there was still a lot of innovation (something you seem to be missing in justifying that these somehow belong in the same category as 1996).

1984 is memorable not because of any competition between Mondale and Reagan (there wasn't) but because it was a landmark election that showed the success of conservatism. It is the Republican 1936, full stop. And the media run up to election day was pretty interesting compared to say . . . . 1996. Don't forget the Democratic Primaries, that brought memorable appearances by Gary Hart, Jesse Jackson, and crew.

Again, your reasonings, which seem to only involve analysis of electoral results and not the actual history behind the races, are flawed if you seriously think any of these (besides 1956) were as bad/boring as 1996. 1996 brought nothing, NOTHING, of interest. If you think it did you either don't remember it (like everyone else), come from a town where the local student races generate a load of publicity, or thought Gigli should've won an Oscar.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Rooney on March 09, 2014, 08:53:51 PM

#51: The Election of 1988

()

Coming in at number fifty-one is the last election of the Reagan Years. In 1988 the United States was given an uninspiring choice between a career resume builder and a liberal Northeastern governor. The election was one in which it appeared that it would emerge as a climactic struggle between Reagan’s America and the days of Roosevelt and Johnson. In the end it turned into a trivial pursuit.

By 1988 President Reagan was a great deal like Thomas Jefferson in 1808: personally popular but dogged by policy failures and political scandal. While Reagan’s inflationary spending and tax policies continued to prop up the economy the Republicans could continue to claim that it was “morning in America.” Vice-President George H.W. Bush, the son of a senator and a walking resume in a suit, scrambled to claim the mantle of the Reagan Revolution. Conservatives at the National Review sighed at the thought of the man who called Reagan’s economic program “voodoo economics” leading the crusade to vindicate supply side theories. Senator Bob Dole, Congressman Jack Kemp, former acting president Al Haig and the Reverend Marion “Pat” Robertson (as well as Du Pont of Delaware and some others) attempted to steal the Gipper’s crown from his nerdy veep, but in the end the GOP Primary was fairly tame. Following Dole’s win in Iowa, which is hardly that important to winning the nomination in retrospect, Bush steamrolled his neophyte opponents and won the nomination in New Orleans. It is to be applauded that Bush selected Senator Dan Quayle as his running-mate and in doing so introduced a little anarchy to what was a fairly even headed Republican primary. This adds a little spice to the campaign soup. One also needs to applaud Bush’s “Mr. Rogers” like reading of the Peggy Noonan speech he was given. The “read my lips line” is a classic no matter how silly it sounds.

This campaign was greatly helped by the adorable efforts of the Democrats. In 1984 the Reverend Jesse Jackson had run a spirited campaign for the presidential nomination and was an early leader for the party’s presidential nod. Former Senator Gary Hart could easily have made the Democratic Primary as boring as the GOP contest had he been able to control his libido. Thank God that most politicians have no self-control. The meltdown which Hart was kind enough to show the nation from 1987 to 1988 entertained the sadistic amongst us almost as much as the crying fit that Congressman Pat Schroeder volunteered to the 1988 Democratic Primary freak show. I do not know what was in the water in the Rocky Mountain State in 1988 but one can only thank the god of campaigns that it was present in the H2O. Jackson emerged as the front-runner but was not alone after Hart sunk along with his Monkey Business. The primary struggle between Jackson, technocratic Massachusetts Governor Mike Dukakis, Senator Al Gore, Congressman Dick Gephardt, bow tie enthusiast Senator Paul Simon and Senator Joe Biden was very memorable. Biden, a well-known piece of skin with a grin stretched over it, decided that he did not want to take time to write his own speeches. Al Gore was insulted when a heckler told him he would make a really good vice-president. The 1988 Democratic Primary remains the primary in which the most candidates won states and delegates. That is exciting and it shows what a weak field of candidates can really do when they are unleashed on the nation. When Dukakis finally emerged as the bloodied primary victor at the Democratic Convention in Atlanta he held off Jackson’s delegates and then declared that the election was about “competence.” Dukakis then went on to prove he had none.

The 1988 campaign is a disappointing one because the general election was very bad. To be fair Dukakis, who started out with a huge lead in the polls, started out the race by pointing to the social and economic disparities of the Reagan years and these attacks seemed to stick. Bush was down by 20-points following the Democratic Convention. That is when the GOP had a brainstorming session and came up with a brilliant strategy that won them the race but place the 1988 campaign at number fifty-one on the list. They attacked the ACLU, spoke about the Pledge of Allegiance and scared middle class, suburban voters with a scary looking black man named Horton. One had to give a hand to Atwater and Ailes since they are the men who saved the boring Poppy Bush from himself. Steady attacks on Dukakis’s patriotism and performance as governor led to his campaign going into a steady downhill spiral of failed PR touchups. While the helmet and the tank are iconic the writer can hardly claim that they place the campaign in the upper echelon of elections.

As the Bush campaign toured American flag factories in New Jersey and Senator Symms of Idaho accused Kitty Dukakis of burning American flags the Dukakis campaign proved itself unable to respond to the attacks. One needs to remember that at this time there was a farm crisis, an ending Cold War and a saving and loan crisis. All of these issues could have been major focuses of the Dukakis campaign but he allowed Bush’s men to set the agenda. This is to the credit of Bush’s men but that does nothing to further the rankings of this campaign on the list. The debates themselves produced some memorable lines. Bush’s reference to Dukakis as “the ice man” and Bentsen’s well received, but ultimately useless, “Jack Kennedy” line are fond to remember but they did not have any effect on raising the campaign’s rhetoric or changing the results of the race in November 1988.

In conclusion, Bush won the election of 1988 as was to be expected. He was the vice-president to a fairly popular president. He was one of only four vice-presidents to be elected directly to the top job from the second job. This was to be expected when the campaign offered so little serious discussion of issues, very few surprises and an incompetent opponent who blew a big lead. The election of 1988 was a game of pursuing the trivial and this is why it places at fifty-one on this list.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Oswald Acted Alone, You Kook on March 09, 2014, 09:22:50 PM

Will 1860 be number one or not?

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: True Federalist (진정한 연방 주의자) on March 09, 2014, 10:48:52 PM

Will 1860 be number one or not?

Don't be so impatient! Altho personally I doubt it would be as Lincoln's victory in electoral college was widely expected by election day whereas in 1800, 1824, 1876, and 2000 it wasn't until well after election day we knew who would be President. I'd think 1860 would be in the top ten, but not number one.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: FEMA Camp Administrator on March 09, 2014, 11:57:22 PM

Will 1860 be number one or not?

Christ, boy, we're in the 50's! We've got quite a ways to go, young one, and other contenders (though some are more viable than others) would have to be 1824, 1968, 1912, are out there.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Rooney on March 10, 2014, 08:59:38 PM

#50: The Election of 1904

()

Landing in at number fifty on this list is an election that involved the enigmatic personality of Theodore Roosevelt. Why is it at number fifty then? It is because TR failed to show any personality during the campaign. As the sitting United States President Roosevelt stayed in the White House and did not utter a word on his behalf. While TR’s presence in the 1912 contest places that campaign in the upper echelon of contests his refusal to break tradition and campaign as the incumbent place his triumphal reelection at number fifty.“Czolgosz, Working man, Born in the middle of Michigan, Woke with a thought And away he ran To the Pan-American Exposition In Buffalo, In Buffalo!” So goes the “Ballad of Czolgosz” in the great Stephen Sondheim’s classic musical Assassins. As soon as the anarchist Czolgosz had unleashed the bullets from beneath his handkerchief it was only a matter of time before the eccentric Renaissance man Vice-President Roosevelt became the man in the president’s chair. In his first three and a half-years in the White House Roosevelt battled J.P. Morgan, ended a coal strike, overthrew Colombia’s government in Panama and started a legal war with Standard Oil. With such an active and controversial first term one could reasonably hope for a great reelection struggle for the president who had turned the nation on its head. This, however, proved too much to be expected.

The Old Guard of the Republican Party could have made this election a good one at the Republican Convention. Angered by Roosevelt’s usage of government power against business conservative elements in the Grand Old Party maneuvered to contest TR’s nomination with the person of Senator Mark Hanna of Ohio; this plan never materialized. Hanna, a Northern Ohio businessman who was friendly to his own laborers but not to organized labor, would have been an effective opponent to run against TR as he was a business conservative and also an anti-imperialist. The epic struggle between Hanna and “that damned cowboy” never came to be as Hanna passed away in February 1804. The Old Guard toyed with running Speaker of the House “Foul Mouth” Joe Cannon against TR but Cannon figured he already had more than enough power as the master of the House. At a prosaic Republican Convention in the usually raucous Chicago, Illinois, all 994 delegates voted for Roosevelt for president and the bearded iceberg Senator Charles Fairbanks for vice-president.

Death would be an enemy to this election. Not only did the Grim Reaper rob election junkies of a great Republican Convention battle it also cleared away the strongest opponent Teddy Roosevelt could have faced in the general election. Former U.S. Naval Secretary and millionaire financier William C. Whitney was the frontrunner for the Democratic nomination in 1902 and 1903. A prominent Bourbon Democrat (though he never called himself that name as it was considered odious), Whitney would have been a fine opponent to oppose Roosevelt. A gold Democrat and anti-imperialist, Whitney had the strong support of both urban and rural Democrats. Then came the nasty winter of 1904 and in February 1904 Whitney died. The remaining Democrats in the campaign were all underwhelming. Judge Alton Bruce Parker, a solid jurist on the New York Court of Appeals, emerged as the Bourbon Democrat choice and the front-runner. Former President Grover Cleveland, who had worked with a young Assemblyman Theodore Roosevelt when he was governor of the Empire State, refused to enter the contest. 1896 and 1900 nominee William Jennings Bryan, “the Boy Orator of the Platte”, also withdrew from the race leaving a free-for-all as the successor for the populist Democratic mantle. Absentee Congressman and newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst and Senator Francis Cockrell of Missouri competed with each other for populist Democratic backing. In the end, however, none of these three candidates do anything to heat up the campaign. While Hearst is an engaging and incredible figure in American history his campaign for president was disjointed and disorganized. With the sachems of Tammany Hall and Mayor George B. McClellan, Junior, opposing Hearst and supporting Parker there was no doubt whom would carry the delegates of the Empire State and with them the party’s nomination. At the St. Louis national convention Parker won an easy victory over Hearst and to add to the fun of this race the 80-year old former Senator Henry Winter Davis of New Jersey was named as vice-president. Davis is, to date, the oldest major party candidate ever nominated for national office.

Neither of the primaries offered a great deal of surprise nor did the general election. If Hearst had been the nominee it would have been unique to see the force of his personality and media empire unleashed on Roosevelt. A full court press by Hearst against TR might very well have chased Roosevelt out of the White House and led to a truly epic campaign. However, the polite and conservative Judge Parker refused to point out any differences between the incumbent and himself. When one reads the party’s opposition platforms one can understand why Parker chose not to say much: there were few differences. Big business pumped money into the Roosevelt campaign. H.C. Frick and E.H. Harriman donated a combined $400,000 to TR. When TR targeted U.S. Steel in 1905 Frick commented: “We bought the son of a bitch and he did not stay bought!” Roosevelt later denied that he had sought Harriman and Frick’s assistance. The Democrats were broke and were unable to run a national campaign.

The only drama of the general election came from Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World which accused U.S. Corporate Commissioner George Cortelyou of accepting bribes from the beef, oil, steel, sugar, coffee and paper trusts. Judge Parker gave a speech in October 1904 assaulting “Cortelyouism” and TR responded by calling Pulitzer’s attack “blackmail.” The scandal did not catch on and was quickly forgotten. This was unfortunate because in 1911 the charges would prove to be correct. Oops!

In the end the election of 1904 was a predictable curb stomp. Theodore Roosevelt won a landslide victory, taking every Northern and Western state. Roosevelt was the first Republican to carry the state of Missouri since 1868. The reason why this election is rated low while elections such as 1936, 1964 and 1984 are rated much higher is because this landslide election left very little to the imagination. Two primaries were ruined by death as was the general election. Exciting candidates either were claimed by death or failed to gain nomination. The greatest drama of the election came at the end of the campaign when Teddy Roosevelt announced that he would not seek reelection in 1908. That little address proved to be the greatest speech Roosevelt ever lived to regret. Something can be said for an election where the drama occurred after the votes were all counted and the shouting, what little there was, ended.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Rooney on March 11, 2014, 07:31:00 PM

#49: The Election of 1956

(

The election of 1956 lands at forty-nine on the list. This election was a rematch of one of the truly great contests in American history. In 1952 victorious Supreme Allied Commander Dwight Eisenhower gave into the pressure and admiration of the American people and allowed himself to be made into a presidential candidate. An epic Democratic Convention elevated Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson to the unenviable position of opposing the war hero. Stevenson proved himself to be a scrappy underdog and made the campaign a memorable bout. 1956 was very much the opposite. While it had some moments of suspense and drama the entire election was a very mild affair. This is quite disappointing considering that the world was on fire in 1956.

President Eisenhower had made it known to his wife that he wanted to only serve as single term in office. A series of health related shocks and surgeries in 1955 seemed to edge him that way. In March of 1956, after “facing the sheer, God-awful boredom of not being president”, Ike announced he would seek a second term in office. One potential area of dramatic tension in the Republican Primary came with Eisenhower’s strange ideas about reelection. He had told Press Secretary James Haggerty that he had visions of ditching the GOP and running as a “third choice” candidate. He had toyed with naming his brother Milton as vice-president. He also brought up the name of Treasury Secretary Robert Anderson and even Democratic Ohio Governor Frank Lausche. When Milton told Ike that this dream was absurd Eisenhower attempted to pry the devious Vice-President Richard Nixon from the chair one heartbeat away by naming him Defense Secretary. Despite the fact that the vice-presidency isn’t worth a bucket of warm piss Nixon knew that it was his best chance for the presidency. At the GOP Convention in San Francisco gadfly former “Boy Governor” Harold Stassen attempted to lead a conclave for former Massachusetts Governor Christian Herter. However, this did not amount to a heal of Boston baked beans. The 1956 Republican Convention at the Cow Place in San Francisco was a real downer. This was not to be repeated when the GOP came back in 1964.

The 1956 contest is greatly aided by the Democratic Primary. Stevenson had been an all but announced candidate for the 1956 nod as soon as he conceded the 1952 election. Known for his whit (“Eggheads of the world unite, you have nothing to lose but your yolks!”) and intelligence, Stevenson was the darling of the progressive, internationalist wing of the Democratic Party. The enigmatic former First Lady of the World Eleanor Roosevelt gave vocal support to “the Man from Libertyville.” Stevenson, however, was forced to battle for the nomination. In 1956 there was to be no draft. This lessens the drama but ups the campaign joy. His major opponent was the comic book crusader Senator Estes Kefauver. After taking on the crime families of New York, Harry Truman and Tales from the Crypt, Kefauver was back to make his second run for president. The battle between Kefauver and Stevenson was a great one in the history of Democratic Primaries. Kefauver’s upset wins in New Hampshire, Indiana and Minnesota allowed him to stay into the battle all the way to June. Stevenson was thoroughly disgusted by the primary campaign. In the pivotal California primary he was forced to don blue jeans, a bolo tie and a ten-gallon Stetson hat in a parade. Following the parade he threw the tie off in disgust and loudly declared for all to hear: “God, what a man won’t do to get public office!”

The additional wildcard of millionaire New York Governor W. Averell Harriman, the candidate backed by the exiled Harry Truman, adds a great deal to the 1956 contest. In May 1956 Stevenson and Kefauver also squared off in one of the first televised presidential debates. These factors led to a good convention in Chicago. What added even more spark to the election was the open battle for vice-president. Senator Kefauver faced off against the youthful, if unaccomplished, Senator John Fitzgerald Kennedy of Massachusetts. While JFK’s father Joe told him not to touch the vice-presidency because “Stevenson is a loser” Kennedy was able to make a strong bid for the nod. It took two ballots for the experienced Kefauver to dispatch of the neophyte Kennedy. The emergence of the doomed Stevenson-Kefauver ticket is a great election story and one that adds a great deal of drama to the campaign.

“Eisenhower stands for “gradualism.’ Stevenson stands for ‘moderation,” comedian Mort Stahl said during his San Francisco night club act. “Between these two extremes, we the people must choose.” Stahl’s bit of gibe says a great deal about the election of 1956. The year was not a placid year but the election was. While Hungary was invaded by the Red Army and French, British and Israeli paratroopers landed in Egypt, neither military event played out a great deal in the election. Stevenson did not let the fact that he was down badly in the polls stop him from campaigning hard. He attacked Nixon as unfit for the presidency in four years. He came out for farm relief and nuclear arms limitation. He openly questioned the intelligence of the “hidden hand presidency.” Eisenhower opposed Stevenson’s call to end the draft.

Despite his strong campaign, Stevenson never stood a chance. When Stevenson asked a farmer who was upset about Ike’s farm policy, “But why aren’t people mad at Eisenhower?” the farmer replied: “Oh! No one connects Ike with his Administration.” A campaign that could have been a close one if Nixon had taken on Stevenson was a landslide because the incumbent was such a beloved figure. Stevenson is to be applauded for trying to make the election a contest but in the end Eisenhower was too much of an institution to be toppled. Perhaps Chicago businessman and NFL hockey team owner “Dollar” Bill Wirtz put it best: “If the Electoral College ever gives an honorary degree, it ought to go to Adlai Stevenson.”

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Rooney on March 12, 2014, 08:51:32 PM

#48: The Election of 1928

(

Landing at number forty-eight on the list is the election of 1928. President Coolidge called it quits in South Dakota in 1927 leaving the path open for hos progressive (if meddlesome) Secretary of Commerce Herbert Clark Hoover. Hoover steamrolled his way into the GOP nomination and over big city New York Governor Alfred E. Smith. It was the election which pitted the East Side against West Branch.

The Republican Convention in Kansas City, Missouri, was a repeat of the 1924 affair. Hoover, though he underperformed in the primaries, was the easy winner on the first ballot. Governor “Pockets” Frank Lowden was the only opponent who seemed he could take on Hoover. However, he dropped out of contention the day before the convention opened. With Coolidge refusing a draft and Vice-President Charles Dawes an unpopular, pompous jackass there was no one who could stop the Hoover tidal wave. “Who but Hoover?” was more than just a slogan; for Old Guard Republicans it was the dim, sad reality. Coolidge’s “Wunduh Boy” was an easy winner in both the primary and the general election. A hero for his work in Belgium during World War I, leading the 1927 relief of the Mississippi flood and meddling in many free market affairs as Commerce Secretary, Hoover was a national figure who was popular with the populace. His very name was a synonym for trim efficiency: “I’ll never learn to Hooverize when it comes to loving you.”

The Democratic Convention was a good deal more interesting because the candidate who emerged as the nominee was as different from the straight laced Quaker Hoover as night and day. Ebullient and friendly, Governor Alfred Smith had no education but did not need it to become the multi-term governor of the Empire State. A fixture of Tammany Hall and a hard drinking Irish Catholic, Smith grew up on the sidewalks of New York and did not hide from the fact. While more closed minded neighborhoods in Kansas and Iowa hardly were taken by Smith, the cigar munching politico was beloved by his fellow urban Catholics. At the Democratic Convention in Houston, Texas, Smith did not face serious opposition. Congressman Cordell Hull and Senator James Reed ran as pro-prohibition Protestants and were both soundly defeated on the first ballot. The great drama that came from the Democratic Convention was that a Roman Catholic was placed at the top of a national ticket from a major party. Smith, who had sought the nomination in 1920 and 1924, took the prize but in the end would prove to be hardly a match for the Republican Roaring Twenties. In the end the boulder donning guv was Hooverized by Main Street.

One of the great myths of the 1928 election is that Smith lost because of his religion. He lost because no Democratic could win in 1928 with a booming Stock Markey and easy credit sustaining the economic bubble known as the Roaring Twenties. However, his religion did not help his cause. Smith’s campaign manager was businessman John J. Raskob, a wet Catholic, and his campaign song was the diddy “The Sidewalks of New York.” These campaign choices only alienated Middle America from the Democratic standard bearer. Smith made it clear that he believed the separation of church and state and Hoover, to his credit, did not directly attack Smith’s religion. In the end, however, he also did not do a great deal to stop the attacks. The Protestant assaults on Smith’s religion add some bigoted suspense to the race but in the end the election was never so close that religion could turn it against either candidate. “Well,” Smith is said to comment after the election was said and done, “The time has not come where a man can say his beads in the White House.”

In the end the 1928 election involved two unique candidates. It is by no means a boring election but compared to other races it does not register as one of the greats. Hoover’s victory was only a matter of time. Democratic attacks on him failed to register. The production of a falsified photo showing Hoover dancing with a black woman in Mississippi did not bring the Solid South or border states back to the Democratic fold. The final election results are unique, no doubt. Hoover carried such Democratic standard states as Texas, North Carolina, Florida, Virginia and Tennessee. Smith, on the other hand, carried nine out of the top ten most populous American cities. This is a result that matters. In 1932 the South would head back to the Democrats but the GOP has never managed to reclaim the urban environments which clamored to Smith. The Coolidge prosperity is what won the election for Hoover as well as the Great Engineer’s personal popularity. 1928 was an election in which GOP newspapers asked, “Smith or Hoover? Who would you want to run your business?” As happens so often, the interview process was not needed as the job was already safe for one applicant.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Rooney on March 15, 2014, 04:00:35 PM

#47: The Election of 2004

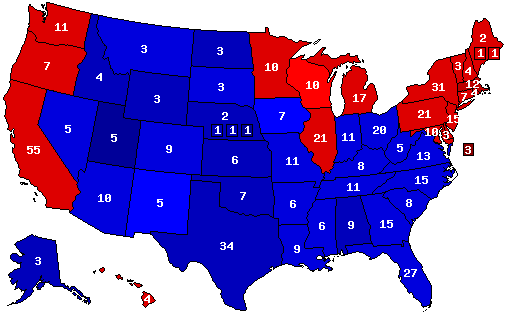

( )

)

Landing at number forty-seven is the reelection victory of George W. Bush. Following the free-for-all that was the 2000 election the general canvass of 2004 was hardly as exciting. This is not to say that Bush’s reelection lacked suspense and drama but the cast of characters assembled was uninspiring. In the end a seemingly back and forth battle had a straight forward ending that could have been predicated from the start.After his highly unique election in 2000, President George W. Bush had managed to deficit spend his political capital into two tax cuts and two wars. The genesis of the global “War on Terror” allowed for him to grab unimagined presidential powers. The Patriot Act, National Security Letters, indefinite detainment, extraordinary rendition and billions in overspending were all given the thumbs up by a Congress composed of limited government Republicans. These decisions proved to be, uniquely, popular and polarizing. The haughty left mocked George W. Bush as “chimpy” and questioned his literacy, but as they chortles down their herbal teas a Neoconservative junta in the West Wing set about building up the “Bush Brand” for the 2004 reelection bid. Karl Rove and Andy Card proved highly adept at molding the illegal Iraq War into a worthy struggle. Despite rising casualties, no WMDs and the fact that the new Iraqi “government” was held up by American bayonets, the Mad Men of the RNC were able to sell the war to the American people as just and necessary. Polls in January 2004 showed both Bush and his war polling at 51% of higher in terms of approval. The economy “grew” steadily, with unemployment so low Hubert Humphrey would have called it “full employment”, as the Neoconservative junta built up a persona around Bush that would prove unbeatable in the general election. The “crazy cowboy” image Bush had attained in Europe was effectively spun as a positive. Bush, who fancied himself an international sheriff of sorts, was portrayed the leader of a posse who were going to throw the noose around the neck of terrorist leaders and their supporters in world capitals throughout the Middle East. In the United States of 2004 this image was a hard one to beat. The Democrats needed to produce an unbeatable candidate who could counter this image and show the nation that the U.S. needed to reject the Neoconservative sheriff’s posse. The man they nominated was not the right man for the job.

The election of 2004 is made disappointing because the eventual Democratic nominee was hardly the correct foil for the Bush image. Senator John Forbes Kerry (JFK?) was not a bad nominee by any means. He was a solid Great Society liberal who was hawkish on foreign affairs. He could debate well and, while not a soaring public speaker, had competence on the stump. His wife was loaded with cash and he had been a senator since 1985. His Vietnam War experience and three Purple Hearts technically should have appealed to defense minded swing voters and independents. This leads to the question: “If Kerry was such a solid candidate then why was he not the best man to take on the president?” The answer is that Kerry was far too much like Bush. The 2004 election falls low on the list because there was little to no contrast between the two candidates. They argued about tax cuts but only in the sense of how much money the rich should be given back. They disagreed on the Iraq War but only in terms of how the war should be fought, not whether it should have been fought. Kerry’s vote for the Iraq War Resolution coupled with his selection of pro-Iraq War Senator John Edwards as his running-mate effectively made Iraq a null-and-void issue. The Kerry/Edwards campaign was simply a non-neoconservative Republican campaign. Yes, Kerry gave lip service to liberal standards like health care and the minimum wage but his campaign never really found an issue to run on. In the end Kerry was simply “Not Bush.” That type of a campaign can be effective but it is hardly memorable. Memorable campaigns give people something to vote for, not just against.

The great tragedy of the 2004 election is that in 2003 it looked as if the race was going to be an epic struggle of the neocons versus the doves. Powered by youthful supporters and the internet, former Vermont Governor Howard Dean looked to be the likely opponent to take down King George the Second. I will admit that I was a “Deaniac” in 2003 so this part of the post may seem biased…because it is. Governor Dean was not a perfect candidate. He had the tendency to ramble, get off message and say things that could be easily misconstrued by the media. Dean was also rabidly leftist on issues like war, health care and the economy. The Bush Campaign was well prepared to oppose Dean. The campaign that Rove and Card had worked up to battle Dean was akin to Nixon’s 1972 smear fest against Senator George McGovern: “Acid, amnesty and abortion.” Dean, however, showed he was willing to fight back. An election between Bush and Dean would have been a great contest between two different ideologies. While Dena was a pragmatic centrist as governor, his presidential campaign was a left-wing dovish crusade against the Neocons in the White House.

Would Dean have won? This is doubtful. The Democrats felt the same way. Kerry appeared to be more “electable” in the general election. Dean rubbed people the wrong way, or so it appeared. Kerry was more center-left and did not appear weak on defense. The 2004 Democratic Primaries proved to be anti-climactic. Kerry won Iowa and New Hampshire. While John Edwards and General Wesley Clark won a handful of contests Kerry was never seriously challenged from January 2004 until the start of the general election in July 2004. This is no good for campaign ratings.

It can be argued that the general election of 2004 was exciting because it came down to a few key states. The struggle for Ohio and Pennsylvania are both case studies in voter outreach and campaign organization. Yet in the end Bush won Ohio and Kerry took Pennsylvania, both of which polls generally pointed to in the closing days of the campaign. The Real Clear Politics average of polls in Ohio, for example, showed Bush leading by 2.1%. He ended up winning the state by about that margin. While the campaign’s polls were close the eventual victory of Bush was a sure thing throughout much of October.

The October Surprise that year was the October 29, 2004, release of yet another Osama bin Laden video. The media hyped this up as a main reason Bush was reelected but it was not. By October 29, 2004, Bush led in the national polls despite three weak debate performances.

Kerry Campaign was simply unable to catch fire with the nation’s voters. The main reason why 2004 falls in at forty-seven is that it offered little surprises. In the Democratic Primary Kerry won easily. He was able to revive a dying campaign, that is true, but he took the ball and ran it across the line with ease once his campaign was up and running. The Republicans offered no surprises the whole election. Bush fell below 50% approvals occasionally and Kerry led nationally at different points but in the end the incumbent president won reelection. The closeness of the race is hardly a reason to place it high on the list. Close elections can be as anti-climactic as landslides if the candidates are not interesting. The election between Kerry and Bush was a lot of shouting over very few differences.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Oswald Acted Alone, You Kook on March 15, 2014, 04:23:13 PM

That last sentence is a nice summary of some of these low-ranked elections.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: SPC on March 15, 2014, 05:10:41 PM

I'm guessing 2012 is #46 then.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Snowstalker Mk. II on March 15, 2014, 05:55:12 PM

I'm guessing 2012 is #46 then.

Nah, 2012 was honestly pretty fun in both the primary season and some debate moments.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: True Federalist (진정한 연방 주의자) on March 15, 2014, 11:45:32 PM

I'm guessing 2012 is #46 then.

Nah, 2012 was honestly pretty fun in both the primary season and some debate moments.

2012 should be #27 since 9+9+9 = 27 and it can't be #47% now.

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Rooney on March 16, 2014, 09:04:41 PM

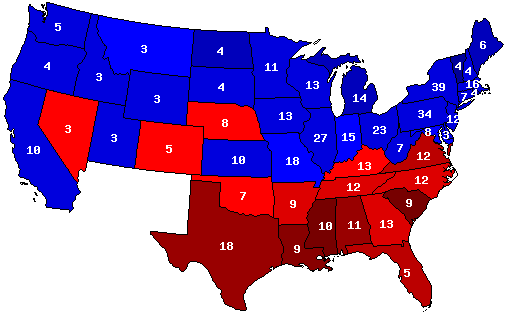

#46: The Election of 1908

( )

)

Winding up at number forty-six on the list is the battle of the two Williams. In 1908 the eccentric and enigmatic Theodore Roosevelt sat out the race and allowed his friend and protégé

William “Big Bill” Taft to take the reins as the Republican standard bearer. The Democrats plodded out well-worn candidate William Jennings Bryan. The boy orator was now losing his hair and his prestige. The Great Commoner, the old war horse, stood no chance against Taft, the Secretary of War.

“What is the real difference between the Democratic and Republican Parties?” puzzled Joseph Pulitzer in 1908. The war lover was correct to puzzle until his puzzler was sore because there were precious few differences between Taft and Bryan on most important public policy issues. The trust busting, railway regulating, interventionist government of Teddy Roosevelt was the only issue of the campaign and both Bryan and Taft supported the reforms. “The voters,” declared the conservative Washington Post, “refuse to go into hysteria over the puny little questions that divide the two parties.”

On the Republican side there was precious little struggle. On the night of his great victory in 1904, TR had announced he would not be a candidate in 1908. Roosevelt famously wrote to military advisor Archibald Butt that he would “gladly give a hand” if he could take back those words. Roosevelt loved the presidency and the press loved Roosevelt. His big teeth, oversized mustache, high pitches voice and bombastic energy made for great print copy. Who could take his place? The answer was none but Roosevelt made sure his protégé was given the position. The friendly and magnanimous Secretary of War William Howard Taft was the only serious candidate for the nomination in 1908. It is a unique fact that 1908 was the first election in which statewide presidential primaries came into vogue. However, they made precious little difference in either of the major party’s final nomination. Conservatives in the form of Joe Cannon and Joseph B. Foraker vied against Taft as did another Roosevelt man: Senator Philander Knox. Taft, prodded on by an ambitious wife with an appetite for power to meet Bill’s for food, entered into several state primaries and won most of them. The legal minded Taft won the party’s nomination with over 700 delegate votes on the first ballot at the convention in Chicago. The greatest excitement of the convention was the forty-nine minute demonstration for TR accompanied with the chant of, “For-four-four years more!” Teddy, however, pulled the strings to make sure that Congressman “Sunny Jimmy” Sherman was nominated as Taft’s running-mate mate on the first ballot. As Taft left the convention it was joked that T.A.F.T. stood for “Take advice from Theodore.”

On the Democratic side William Jennings Bryan, the elder statesman of the Party of Jackson, was the only real candidate for the nomination. Bryan was so much the front-runner for the nomination that at the Denver convention his handlers made sure that the demonstration for him lasted exactly one-minute longer than the demonstration Bryan had received for the “Cross of Gold” speech in 1896. “Are we over time yet?” they asked each other as they checked their pocket watches. After being paired with perennial loser John W. Kern as his running-mate, the ticket of perennial losers decided to not campaign for the first few weeks. Bryan instead worked on his newspaper, The Commoner, and Kern went home to Indiana to sew wild oats. “Shall the people rule?” Bryan asked. He declared this question to be the “pivitol issue of the campaign” and in the end the people would not rule in favor of him.

The reason why the election of 1908 is placed at number forty-six is because it has excellent candidates but they had very little to argue about. “Hit them hard old man!” Roosevelt had advised Taft. Taft only liked to hit hard when he was playing baseball. He knew that Bryan had nothing to offer the nation that Teddy had not already done. In fact, Bryan made one of the main themes of his campaign the fact that he could bust trusts better than Taft. He argued he was the better heir to the Roosevelt legacy. Taft gave some public addresses but he hated them. He told his wife Helen that the idea of giving his acceptance speech in Cincinnati before a crowd of a few hundred people hung before him “like a dark nightmare.” It is unique to mention that Taft and Bryan had their speeches recorded for the phonograph and played around the nation. However, this did not change the outcome.

Taft beat Bryan and beat him badly. Gadflies commented that everytime Bryan was nominated for president he was nominated in a city further and ruther away from the White House. Some wagged that in 1912 he would be nominated in Los Angeles and in 1920 Manila and in 1924 Shanghai. Bryan himself asked his readers to answer “THE RIDDLE OF 1896” and explain to him why he had lost so badly. The fact was that Bryan scared people. He promised to nationalize the railroads if elected president. This turned the railroad magnates against him and towards Taft. Despite the Hepburn Act and its unpopularity with railway men it was far better than nationalization. Businessmen supported Taft and the people loved Teddy. In the end there could be no other alternative to a Taft victory. Bryan joked that he felt much like the drunken man who was thrown from a bar three times. When the drunk came back a fourth time he proclaimed indignantly: “Something tells me you fellows don’t want me around!”

Title: Re: Rooney's Presidential Election Rankings

Post by: Rooney on March 17, 2014, 08:07:32 PM

#45: The Election of 1936

( )

)

Coming in at number forty-five is the election of 1936. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s massive reelection is an incredible victory for the forces of progressive labor in the United States and a catastrophic defeat for the “me-too” branch of Republicanism. The reason why it lands at number forty-five is simply because the election offered few surprises and the Republican Party failed to learn much from the contest. “There is one issue in this campaign,” FDR told Raymond Moley, “It’s myself, and people must be either for me or against me.” In the end the people would be overwhelmingly for the sunny chief executive.

The New Deal, which Roosevelt promised in the far more memorable 1932 canvas, had not created prosperity. Millions of people still wanted for jobs, housing and food in the summer of 1936. Despite millions in government spending and a strange group of Utopian socialists called the “Brain Trust” trying out their weird societal views for the first time, unemployment was still high and the GDP was still abysmal. However, the nation felt like happy days were indeed here again. FDR’s first term in office is one of the turning points in American political and governmental history. It is an era all to itself in not just government programming but propaganda. New Deal sponsored art, photography, radio and drama programs pumped the idea that the depression was ending into the minds of Americans on a daily basis. The propaganda worked and it worked well. In 1936 millions of Americans felt that the government had saved them from the doldrums of the depression and that they were far better off in 1936 than they had ever been during the Republican 1920s. FDR’s New Deal propaganda machine is to be applauded. It made an election that should have been competitive into a walk for the man who pulled the strings from behind the curtain. FDR was indeed the Wizard of Oz and no one throws the wizard from the Emerald City.

The assassination of Huey “Kingfish” Long stole a fascinating component from the 1936 campaign because the candidacy of the wild Louisiana governor would have made the election fall in the top ten. He had threatened that he would run on his socialistic “Share Our Wealth” platform as an independent in 1936. His 1935 assassination ended those plans and cast the idea of a Long 1936 candidacy into the realm of “what-if.” T. Harry Williams, the incredible historian, has written that Long had no intention of running in 1936 but instead running another candidate under the “Share Our Wealth” independent banner. If this is the case the death of Long does not totally ruin the 1936 race but even a 3rd party campaign from a Long surrogate would have made the election more dramatic.